A lotta latas….but no llamas: Stephen Cornford reports from Peru

Mercanta’s Stephen Cornford takes a journey: 11,265 km long and, 2,500m high.

London – Lima – Chiclayo – Jaen – La Coipa/ Lonya Grande by train, plane, bus and automobile.

As I found on my recent journey to Peru’s North, the Peruvian provinces within which Mercanta works are well-suited to growing delicious coffee. It was my first time visiting this country, and I fell in love despite the paucity of llamas and the disconcerting variability in the definition of a ‘lata’ (the ubiquitous, though variable, receptacle into which coffee is picked).

With clay loam soil, a day to night temperature range between 16 and 20 Celsius and an average rainfall of 1,300m, San Ignacio Province (Cajamarca region) and Utcubamba Province (Amazonas region), Peru, lie high in the mountains, with 70% of land under coffee straddling 1,600 to 2,000 metres above sea level. These ideal natural conditions are compounded by the high rate of Typica and Caturra coffee trees being cultivated in the area.

Peru is a land of small holders organised around cooperatives. 4 out of 5 producers farm on fewer than 10 hectares of land, and the majority of these farms fall between 2 to 5 acres. For most farmers, coffee is their sole source of income. Despite this (perhaps because of it), processing is often rustic. According to local sources, the washed process was only recently introduced in the late 1990’s and came about due to the sales price reaching double that of the natural process (known locally as ‘coco process’). The fully washed method hasn’t fully displaced the old ways, and both are still used to this day.

Parcela Higueron, Union y Fe Cooperative

Parcela Higueron, Union y Fe Cooperative

Peruvian coffee farmers face many difficulties, even today. For example, the weather in the highlands bordering the rainforest is continuously wet and humid. It rains four days a week during the bean growth, maturation, harvesting and drying stages, which can knock cherries off the trees, thus reducing yield. Cherries remaining on the tree often split, opening them up to disease. Even if they make it to the wet mill so far unscathed, uneven drying caused by these same weather patterns can strip them of quality. In order to address the drying issues, in the La Coipa district (San Ignacio Province) solar dryers have started being installed since 2008. This goes a long way towards mitigating these difficult circumstances, but it still requires a great deal of painstaking attention to detail during the drying phase. Another problem is pests: broca (coffee borer beetle) and coffee leaf rust are hitting traditional varieties hard below 1,600m, prompting many farmers to switch their land over to more resistant Catimor strains. These issues aren’t specific to Peru, of course: they are becoming more commonplace around the world. Nonetheless, they are felt immediately by Peruvian coffee farmer, who are struggling to preserve their way of life while trying to earn a living in these changing circumstances.

Lorenzo Cruz built Stephen C his own LODGE!

La Coipa with Union y Fe Cooperative

I arrived first in Jaén, via Lima, where Lorenzo Cruz García, the general manager and head cupper of Union y Fe Cooperative joined me, along with our exporting partner, Eric. Union y Fe is a cooperative 220 members strong that covers 738.5 hectares, of which 558.75 ha is under coffee. Together, we made the 4 hour drive over dirt roads to La Coipa. There are no hotels in this rural part of Peru, and the cooperative had never had a visitor before, so Lorenzo built both of us wooden lodges, which was very kind of him and made us feel most welcome.

Processing in Peru is rustic. Fermentation is determined ‘complete’ when a wooden pole stands unassisted in the fermented mass of coffee. When drying coffee, moisture is monitored by either biting the parchment, assessing firmness, or by cutting a bean in half. In the latter case, if one half jumps away from the knife, its humidity is 14-15%; if both halves jump, then it’s below 12%. Even with these simple techniques, the group is producing some great coffee: this year we are finding flavours of flowers, stone fruit, melon and sweetened apple in many of the lot samples we’ve received and, subsequently, contracted.

Coffee is handled on a small scale and travels a long way in Peru. Each tree yields only between 6 and 9 kg of cherry per year, which is harvested over 4 passes per season, each of which can last a few weeks. After harvest, they pulp and ferment several lots an afternoon in batches of 300 – 600 kg at a time. Coffee is dried in solar dryers: wooden structures clad in clear plastic with raised bed/boxes lined with screen. Each box will hold 55.2 kg of parchment. The smallest dryer I encountered had a total capacity of 1,435 kg, which is plenty for most farmers, even at the peak of the season.

Members of Union y Fe, La Coipa

The general manager of Union y Fe was the first person in the region to use a solar dryer, and he is a big believer in their ability to preserve quality in this humid climate. In fact, everyone in the cooperative is required to use solar dyers now – it is a requisite for becoming a member! One issue with the dryers, of course, is that temperature can be difficult to control and coffee can sometimes dry too quickly. At higher elevations, however, the ambient temperature is kept cool and even. This was the case with most of the farms that I was lucky enough to visit.

After drying, the coffee then must travel by horse or donkey through valleys and rainforests for at least an hour, before being loaded into a car, where it will travel another hour or more to the cooperative. Each donkey has a load capacity of 90 kg. With a conversion factor from cherry to green in Peru of approximately 5.5, this means a farmer typically delivers less than four 55.2 kg sacks of parchment to the cooperative per visit. The donkey-transport-system is a pretty major bottleneck.

The harvest can be quite costly to bring in, generally, in fact. Farms typically hire from 3 to 7 workers at a time, and as there are not enough pickers locally in La Coipa, many weekends mean visiting the town square in Jaén to pick up day labourers. There is stiff competition on day rates for pickers so you have to pay good prices or your workforce will leave the following morning to a neighboring farm who they’ve heard is paying more. Most pickers work a 9 hour day, and while they can harvest between 75 and 90 kg a day at the peak of the harvest, quantities towards the beginning and end can be as little as 30 kg nearer the beginning and end of the crop. The labour costs are high compared to the prices most farmers earn. [It should be noted that farmers are not obliged to provide transport BACK to Jaén, which, nonetheless, has not seemed to result in a burgeoning population of pickers in La Coipa].

My time with the cooperative started with a group meeting in La Coipa, with representatives from villages across the area. We covered a wide range of topics, including the importance of GrainPro packaging, their price expectations and costs of production and current problems affecting the area. It was really great to be able to have a conversation with so many people at once, which helps us understand better the local social context of coffee production. After the meeting, we traveled to the village of Machete and the home of Armando Sosa, where we had lunch and explored his farm (commonly referred to in Peru as a parcela).

The following day, we travelled to Vira Vira village for breakfast, leaving before sunrise and listening to ‘Eye of the Tiger’ (pan flute edition) as we took the windy, cliff-hung roads with near-sheer drops to their very end. Reaching the end, we continued on foot for an hour through a valley and up the other side again. We arrived just in time to be greeted for breakfast at Parcela Higeron by owner Jose Rivera Chinguel and the local villagers. Starving after the long journey, the chicken and rice was very welcome!

On my final day with Union y Fe, we cupped two tables of coffee in the morning, which through a mistranslation ended up with some of JB Kaffee’s (Munich) Kenyan coffee – intended as a gift – as a comparator! I made a selection of samples from what we cupped to bring back to the London office to cup with the team and decide what we will buy this year. Some of the most notable coffees will almost certainly find their way around the world, and I’m looking forward to sharing them with our clients.

After cupping, we made our final farm visits in the village of El Cautivo, where we spent time with at the parcelas of Lorenzo Cruz García, his brother and mother. The three are all neighbors and work together to make delicious coffee! I also had the chance to see the very first solar dryer to be built in the district, which was a nice historical curiosity.

Stephen C with a friend from Union y Fe

FIVE Quick Facts about Union y Fe, La Coipa:

1.The average age of a coffee farmer in the region is 35.

2. Pickers ages usually range from 28 – 30.

3. Coffee trees of members are, on average, 15 years old; however, this figure is skewed by the fact there is quite a lot of 50+ year-old Typica lying abandoned due long periods of low prices paid for coffee generally.

4. The average family size is 2 adults and 3 children. Many children travel to the region’s capital, Jaén, for secondary education. They will live with extended family in the city but usually return afterwards to continue the family tradition of farming coffee.

5. The cooperatives we work with are certified organic, and they make their own fertiliser from a mixture of cherry skin (cascara) and Guano de Islas made from the droppings of bats, seabirds and seals from islands in the Pacific. Around 2 kg per tree is applied. Another organic fertiliser commonly used, called Tamo, is made of coffee parchment.

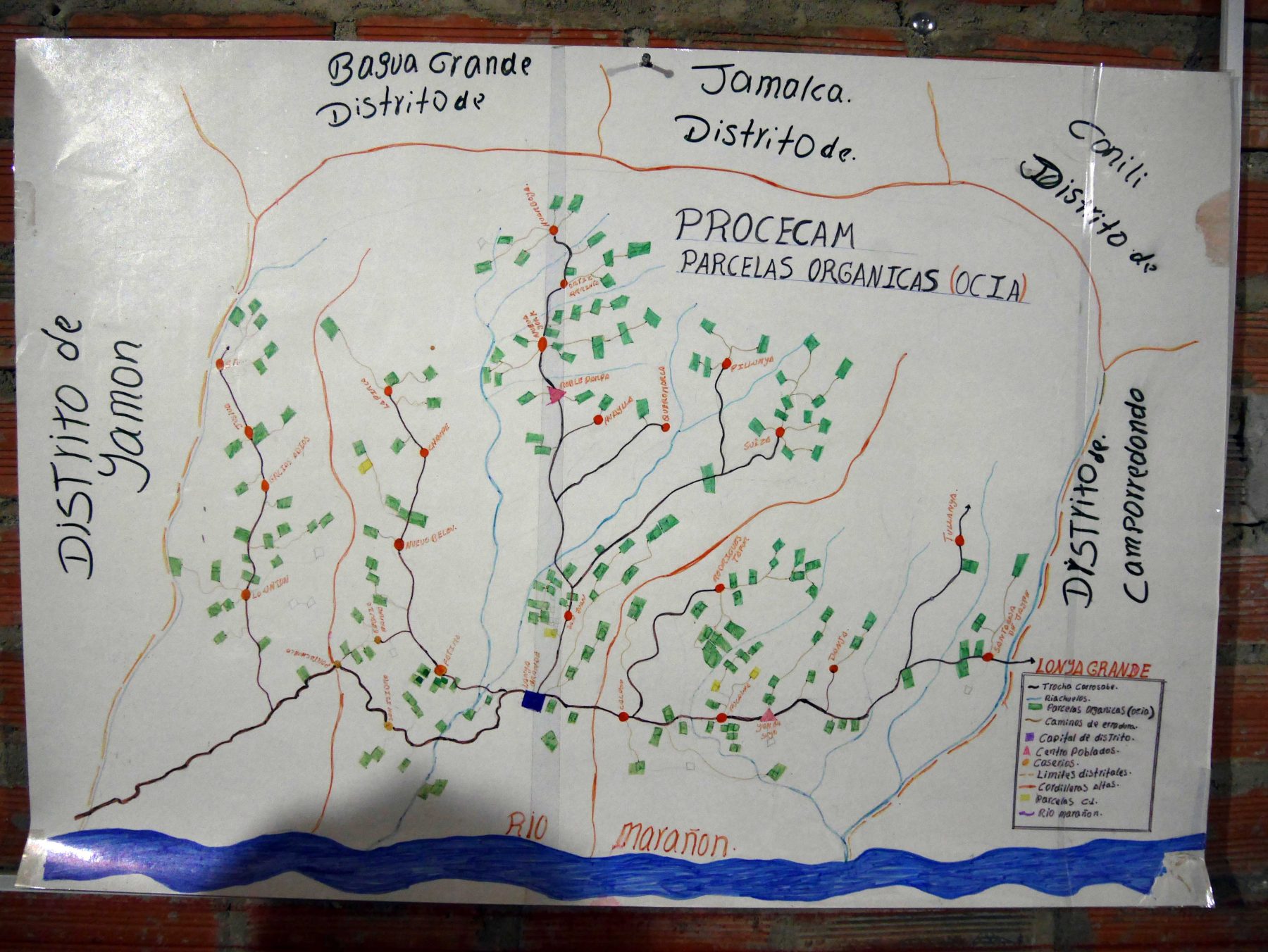

Map of Andes Amazonicos area of service

Map of Andes Amazonicos area of service

Lonya Grande with Andes Amazonicos

After a great trip with Union y Fe in La Coipa, it was time to head over to the nearby Utcubamba Province to visit with the Andes Amazonicos cooperative. The journey to the town of Lonya Grande from La Coipa was seemingly unending. The only way to get there was by road (Stephen Hurst ruled out the helicopter), and I use the term ‘road’ somewhat loosely. The journey was 4 or 5 hours of spine-jolting bumps – but it was worth it.

Andes Amazonicos has a membership of 202 farmers (from the 8,500 farming in this district). They are small by choice and regularly turn away new members, although the cooperative is relatively new (started in 2012). The usual cooperative pattern is to grow in numbers as rapidly as possible; however, Amazonicos decided early on that they prefer to concentrate on working only with quality-focused farmers, quality over quantity. Both the general manager and traceability officer/quality control manager don’t take a salary from the business and work second jobs: Segundo Tiella Hidrogo works as a nurse and Marco Herrera Bustamantes as a builder. They hope one day to be able to take a salary from their work in coffee, but for now it is their passion that drives them forward.

Segundo, the general manager, was the mayor of Lonya Grande district in 2013. He is well-known and was greeted fondly everywhere we travelled. He is a man filled with so much energy and enthusiasm that, to be honest, I found it overwhelming at first. However, on the drive from Jaén to Lonya Grande, his monologue about figures who inspired him – from Theoretical Physicist Stephen Hawkings to inventor Nikola Tesla and, not forgetting his favorite magician, Dynamo – began to inspire me too, and we started to get on fine.

Horse carrying pulped coffee back to the family’s home

On my visit to the region, I witnessed farmers carrying pulped coffee from their farm to their home after pulping but before fermenting. Many farmers live quite distant from where their farm is located, which poses a transport problem. It is seen as more efficient to pulp the coffee at the Parcela, but there usually isn’t enough room for a fermentation tank or drying infrastructure there. Thus, the pulped coffee is loaded into bags and then strung onto the back of a donkey or horse, before being walked down the hills to the farmer’s home and its fermentation tanks. This is not best practice, needless to say; but many rural farmers don’t have access to water at the farm, and it is just a fact of life.

It just goes to show what Amazonicos is up against in their quest for quality. Our first farm visit with the group involved an hour hike through the rainforest to the village of Nuevos Aires – situated under Mount Kuntur Puna. This area is full of old Typica trees, some of which has been growing here longer than I have been alive. The farm we visited was just four years old, and this was the family’s first harvest. I had the chance here to try my hand at picking and pulping coffee, which was enjoyable in a small dose. However, I’ll stick to my day job.

Fruits of the harvest: Before pulping (left) and finishing up drying in Mercanta’s tiny tiny solar dryer

Fruits of the harvest: Before pulping (left) and finishing up drying in Mercanta’s tiny tiny solar dryer

Nilson Silva Diaz’s solar dryer, made from one single tree

The following day, we visited the quality control lab in Bagua Grande – just 17 km away from the collection station and offices. That might not seem far, but to get there, you have to climb up over a 2,500m mountain travelling through the clouds and then back down to sea level to reach the lab, a journey that takes two and a half hours. When I tasted some of the coffees this cooperative’s members are producing, though, it was worth the journey.

My final day was spent at the president of the cooperative’s farm. An interesting fact about his solar dryer was that it was constructed entirely from a single tree and, yet, was the biggest solar dryer I had seen on my trip. I would have loved to see the ‘before’ version. This farm held a few fascinating facts, actually: one I found perhaps too interesting was that the Senamhi weather station is located on his farm, giving you the opportunity to browse temperature, humidity and rainfall on the farm going back years. He also had geisha growing in his nursery.

In both San Ignacio and Utcubamba, commercial coffee is everywhere – drying on tarps spread out over local football pitches and beside the road, walked over by chickens, dogs, and people and sprayed with dirt from passing vehicles. This is, of course, the antithesis of specialty coffee. Most farmers don’t drink coffee, but those who do consume the lower grades and roast them at home in a tiesto, essentially a small clay bowl heated over an open flame. It makes for difficult circumstances when trying to communicate the importance of taking more time with processing, drying and cultivation.

The cooperatives Union y Fe and Andes Amazonicos have a strong focus on producing high quality they have aspirations for the future. Union y Fe is hoping to establish their own dry mill, taking further control of the end-product’s quality. Amazonicos is looking to establish their own cupping lab and to develop an expert team of cuppers so that they don’t have to travel miles and miles to have someone else tell them what their coffee tastes like.

I’m looking forward to making sure that Mercanta is part of their journey.

40 year-old Typica left to grow wild, reaching for the clouds

40 year-old Typica left to grow wild, reaching for the clouds

Special thanks to the villagers and farmers who shared food and conversation on my visit, especially:

Union y Fe:

Machete Village – Armando Sosa – Parcela El Limón

Vira Vira Village – Jose Rivera Chinguel – Parcela Higeron

El Cautivo Village – Lorenzo Cruz García – Parcela Vista Mosa #1

Andes Amazonicos:

Nuevos Aires Village – Mesias and Ivan Tarrillo – Parcela San Francisco

Jusiva Village – Nilson Silva Diaz – Parcela El Cedro

About the Author: Stephen Cornford joined Mercanta in August 2011 and ran Mercanta’s lab for many years before moving into his current position as Account Manager and Coffee Sourcing. He currently oversees sourcing for Peru, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Vietnam.